A stark monument of the past that still waits in pitch-black silence.

When Richard Olsen homesteaded Idaho’s Mammoth Cave in 1954, he thought it would be a great place to grow and store mushrooms. At the time, however, the Soviet Union and their allies were locked in a tense, long conflict known as the Cold War. That’s when the Lincoln County Civil Defense director in Shoshone, Idaho, thought Richard Olsen’s cavern would be the ideal location for housing thousands of people in case the unthinkable happened.

That’s when Richard Olsen was offered a good gravel road from U.S State Highway 75 in exchange for using the cave as a nuclear fallout shelter. Once the agreement was made, the cave was then stocked with enough supplies to sustain over 8,000 atomic refugees.

Sixty-seven years later, the giant volcanic cavern of Idaho’s Mammoth Cave remains a popular tourist stop between Twin Falls and Sun Valley, Idaho. While the supplies the cave once held for nuclear survivors are long gone, Idaho’s Mammoth Cave remains a potential fallout shelter for residents of Blaine Camas and Lincoln Country residents.

Although other bomb and nuclear fallout shelters have been built over time, they are dwarfed in comparison to the massive cavern that still stands in wait just north of Shoshone, Idaho.

That’s when Richard Olsen was offered a good gravel road from U.S State Highway 75 in exchange for using the cave as a nuclear fallout shelter. Once the agreement was made, the cave was then stocked with enough supplies to sustain over 8,000 atomic refugees.

Sixty-seven years later, the giant volcanic cavern of Idaho’s Mammoth Cave remains a popular tourist stop between Twin Falls and Sun Valley, Idaho. While the supplies the cave once held for nuclear survivors are long gone, Idaho’s Mammoth Cave remains a potential fallout shelter for residents of Blaine Camas and Lincoln Country residents.

Although other bomb and nuclear fallout shelters have been built over time, they are dwarfed in comparison to the massive cavern that still stands in wait just north of Shoshone, Idaho.

A Place of Protection Throughout Time

Richard Olsen stumbled on the cave on accident in 1954 while hunting bobcats in the area with his high school sweetheart. At the time, he said, local residents weren’t aware of the giant volcanic cave, except several sheepherders who signed their names on the wall of the cavern in 1902. The cave was also known to past American Indians, who left hollowed out animal bones after they’d consumed the marrow. Other bones of extinct animals such as the Short Faced Bear and other carnivores have also been found within its dirt floor as a testament to all the living creatures that once called the cavern home.

Olsen obtained ownership of the cave and its surrounding land under a federal homesteading program and attempted to grow mushrooms for many years. When the process proved too hard and expensive, he abandoned the project and opened up the cavern as an Idaho attraction for tourists.

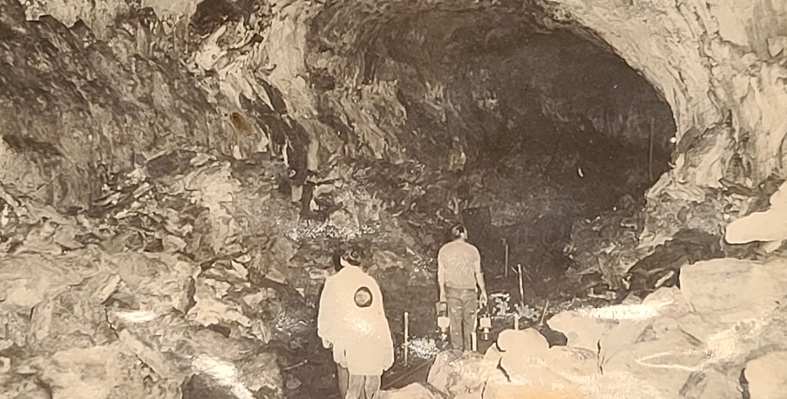

By that time, the Cold War had made its way home to America. The Idaho Bureau of Disaster Services tested Idaho’s Mammoth Cave and rated it 1,000+ – the highest score it had for nuclear fallout protection – and enlisted Richard Olsen’s help building a platform in the cave to hold water and supplies. These supplies were then stocked in the cave by passing them down a human chain of local Shoshone High School students.

Rations included various crackers, wafers, candy, toilet paper, sanitary napkins, water containers, and carbohydrate supplements that would last over 8,000 people two weeks. However, no drills were ever conducted. Instead, the Civil Defense officials knew they’d have to act fast in a hurry if a nuclear attack ever occurred.

They told Richard Olsen that prevailing winds would sweep radioactive fallout to the Shoshone, Idaho area within two to three hours after a nuclear blast over the nearby Mountain Home Air Force Base, located 75 miles west of Idaho’s Mammoth Cave. If the target was somewhere else like Portland, Oregon, the fallout would take approximately one day.

A Place of Protection Throughout Time

Richard Olsen stumbled on the cave on accident in 1954 while hunting bobcats in the area with his high school sweetheart. At the time, he said, local residents weren’t aware of the giant volcanic cave, except several sheepherders who signed their names on the wall of the cavern in 1902. The cave was also known to past American Indians, who left hollowed out animal bones after they’d consumed the marrow. Other bones of extinct animals such as the Short Faced Bear and other carnivores have also been found within its dirt floor as a testament to all the living creatures that once called the cavern home.

Olsen obtained ownership of the cave and its surrounding land under a federal homesteading program and attempted to grow mushrooms for many years. When the process proved too hard and expensive, he abandoned the project and opened up the cavern as an Idaho attraction for tourists.

By that time, the Cold War had made its way home to America. The Idaho Bureau of Disaster Services tested Idaho’s Mammoth Cave and rated it 1,000+ – the highest score it had for nuclear fallout protection – and enlisted Richard Olsen’s help building a platform in the cave to hold water and supplies. These supplies were then stocked in the cave by passing them down a human chain of local Shoshone High School students.

Rations included various crackers, wafers, candy, toilet paper, sanitary napkins, water containers, and carbohydrate supplements that would last over 8,000 people two weeks. However, no drills were ever conducted. Instead, the Civil Defense officials knew they’d have to act fast in a hurry if a nuclear attack ever occurred.

They told Richard Olsen that prevailing winds would sweep radioactive fallout to the Shoshone, Idaho area within two to three hours after a nuclear blast over the nearby Mountain Home Air Force Base, located 75 miles west of Idaho’s Mammoth Cave. If the target was somewhere else like Portland, Oregon, the fallout would take approximately one day.

A Monument of the Past that Welcomes Visitors

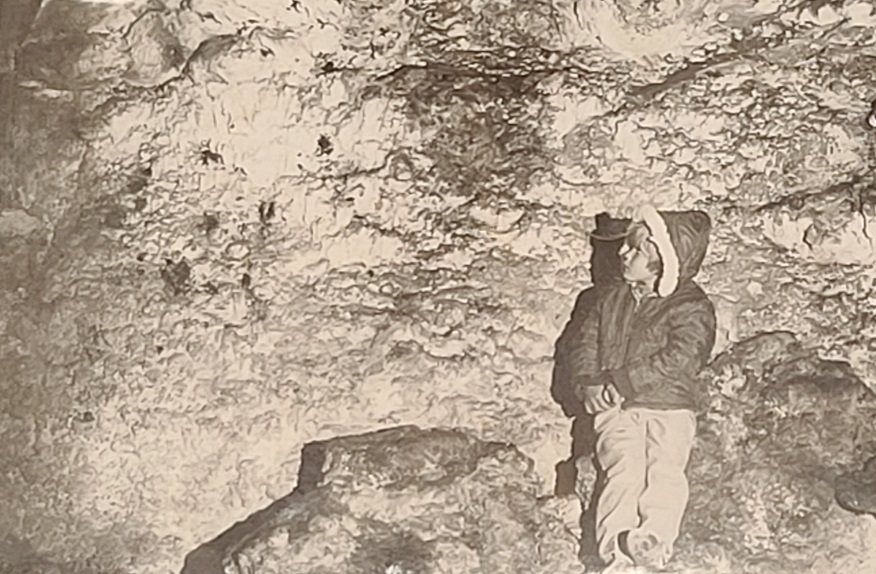

Today, Idaho’s Mammoth Cave is a monument of the past that welcomes thousands of tourists each year from around the world. Visitors are eager to see one of the largest volcanic caves open to the public and to seek relief from the glaring desert sun to its 40-degree subterranean temperature during the summer.

As a famous Idaho attraction, Idaho’s Mammoth Cave is also home to the Shoshone Bird Museum of Natural History built by Richard Olsen, along with a second private museum that will soon be opened to the public. These museums are one of the largest privately-owned collections in the Northwest, packed full of collections featuring four generations of Olsen’s for the world to see.

Also featured are birds and animals from all over the world, mounted to display their colors for close-up educational studies, other native and exotic animals; fish and dinosaur fossils, artifact and anthropology collections, rocks and minerals, along with many others. You can spend hours exploring and still not see everything in one day. Visitors follow a quarter-mile, self-guided tour of the cave, carrying LED lanterns that cast light onto the cavern’s vast walls.

While Idaho’s Mammoth Cave was once filled with supplies to protect and care for residents of Blaine Camas and Lincoln Country against nuclear fallout from an apocalypse that never happened, it still remains available in case nuclear disaster ever strikes.

A Monument of the Past that Welcomes Visitors

Today, Idaho’s Mammoth Cave is a monument of the past that welcomes thousands of tourists each year from around the world. Visitors are eager to see one of the largest volcanic caves open to the public and to seek relief from the glaring desert sun to its 40-degree subterranean temperature during the summer.

As a famous Idaho attraction, Idaho’s Mammoth Cave is also home to the Shoshone Bird Museum of Natural History built by Richard Olsen, along with a second private museum that will soon be opened to the public. These museums are one of the largest privately-owned collections in the Northwest, packed full of collections featuring four generations of Olsen’s for the world to see.

Also featured are birds and animals from all over the world, mounted to display their colors for close-up educational studies, other native and exotic animals; fish and dinosaur fossils, artifact and anthropology collections, rocks and minerals, along with many others. You can spend hours exploring and still not see everything in one day. Visitors follow a quarter-mile, self-guided tour of the cave, carrying LED lanterns that cast light onto the cavern’s vast walls.

While Idaho’s Mammoth Cave was once filled with supplies to protect and care for residents of Blaine Camas and Lincoln Country against nuclear fallout from an apocalypse that never happened, it still remains available in case nuclear disaster ever strikes.

Want to Learn More?

Contact Idaho’s Mammoth Cave by filling out our online form or give us a call at (208) 329-5382. Summer tours are available May through October each year, 7 days a week from 9 a.m – 6 p.m, and admission includes both the cave and museum.